Àdégbòyégà Aróhùnmọ̀làṣé is an artist who doesn’t just make work—he makes meaning. Based in the U.S., his practice revolves around migration, cultural heritage, and the shape-shifting nature of identity. It’s personal and collective, abstract and direct. His tools are as varied as his themes: African wax print fabric, hot glue sticks, rug tufting, enameled copper, beads, pyrography, and words—sometimes in English, often in Yoruba. His pieces hold stories. Layered. Fragmented. Reassembled. Just like people.

What sets Aróhùnmọ̀làṣé apart is how his materials act as metaphors. The wax print fabric isn’t just visual texture—it carries history. It’s cut up, re-stitched, layered again. It becomes a symbol of how identities change without disappearing. Hot glue becomes connective tissue. It binds things together, just like invisible cultural ties do—especially when those ties stretch across oceans and generations.

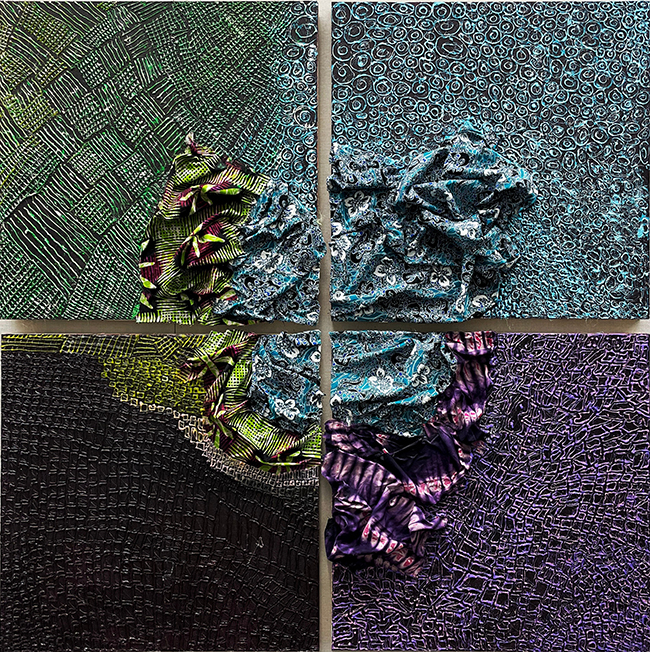

His piece Dance with My Father Again (2023) is a polyptych that reaches back through memory and loss. Inspired by Luther Vandross’ song, the work is built from his late father’s clothes—wax print and tie-dye—broken down and reimagined. It’s a deeply intimate tribute, but it doesn’t close in on itself. Instead, it opens up to broader reflections on ancestry, Yoruba naming customs, and character. Each of the four panels speaks to a facet of his father’s life: character, destiny, lineage, and spiritual transition. Through color, fabric, and Yoruba visual codes, he creates a tactile memorial. It’s art as mourning. Art as honor. Art as conversation.

In Ílè lá n wó ká tó sọ ọmọ lòrukó (The home is where we look when naming a child), Aróhùnmọ̀làṣé brings focus to the meaning behind names and family roots. Here, African wax fabric again plays a central role, but this time layered like a map. It becomes a terrain of cultural memory. The hot glue motifs reflect Yoruba designs that speak of family and structure. Everything is layered, and each layer speaks. The work doesn’t just reference tradition—it’s embedded in it, even as it explores how that tradition migrates and adapts.

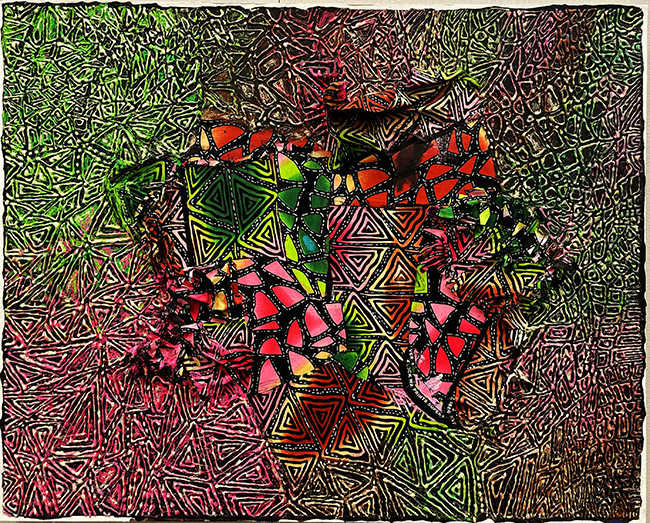

Migration is a recurring theme, and in the Routes and Roots series—Exodus No. 1 and Exodus No. 2—Aróhùnmọ̀làṣé leans fully into it. Exodus No. 1 is a diptych showing the emotional stretch of leaving home and entering unknown futures. The top panel is vivid, almost celebratory—bold wax print patterns speak to the dream of a better life. The lower panel is heavier, dense with enameled copper and glass beads, marked with tribal signs. But as the piece moves upward, things begin to break apart. Marks fade. Patterns loosen. Identity thins under the pressure of assimilation.

Exodus No. 2 continues that story in three parts: homeland, journey, destination. It opens with a celebration of origins—bold, patterned, grounded. The center panel, burlap and tufted, shows struggle. The roughness, the muted palette, the Yoruba patterns, all speak of tension. Then the third panel shifts into something more abstract, more blended. A place where identities mix. Where some parts hold on, and others don’t. There’s no judgment here—just honest reflection. Migration is not just about movement. It’s about trade-offs.

Then there’s Letter to My Unborn Child (2023), a work that combines pyrography, fabric, glue, and acrylic into something both visual and emotional. A letter, written in Yoruba and burned into wood, anchors the piece. It’s not nostalgia—it’s a promise. A bridge from past to future. It acknowledges the shifts that migration brings while insisting on the right to remember and to pass things on. The inclusion of a QR code with an English translation shows how old and new can coexist. Cultural survival doesn’t mean freezing time. It means adapting and continuing.

Throughout all this work, Aróhùnmọ̀làṣé returns to certain ideas: the weight of memory, the plasticity of identity, the unseen threads that connect people to place, to each other, to the past. His materials are never just chosen for their look or texture. They are carefully selected and handled in ways that reinforce his questions about belonging. His use of Yoruba design systems is especially important—these aren’t aesthetic borrowings. They’re declarations. Markers of where he’s from, even as he lives elsewhere.

As both an artist and educator, Aróhùnmọ̀làṣé holds space for these questions—about home, about self, about what we carry with us and what we leave behind. His work doesn’t offer easy answers. It offers maps. Emotional, spiritual, and cultural maps that others might use to navigate their own journeys.

In a time when displacement is increasingly common, and identity is often caught between commodification and confusion, Aróhùnmọ̀làṣé’s work feels like an anchor. Not because it simplifies things, but because it honors their complexity. He’s not just making art. He’s building language—through cloth, copper, fire, and glue—for what it means to belong and to become.