Swiss sculptor and internationally acclaimed artist Not Vital (b. 1948) has emerged as a singular thinker whose practice engages with philosophies of habitat and material life. An incessant traveler and curious explorer, Vital lives a nomadic life that has informed his art and made him a master of the liminal, producing works that refuse categorisation. In line with the publication of his new monograph Not Vital: Sculpture with Skira, we catch up with the artist and the book’s editor and author, Alma Zevi.

A: You’ve lived in a variety of different countries, spanning Beijing, Cairo and Rome, just to name a few. How does travel inform your practice?

NV: Travelling is like breathing. Since my first breath, I have been traveling and this has affected my work, not only in sculpture and painting but also in architecture, which I call SCARCH (Sculpture+Architecture).

A: Dali once famously said, “Give me two hours a day of activity, and I’ll take the other twenty-two in dreams.” Can you talk about your relationship with dreams and the surreal?

NV: To me, Surrealism continues to be the most radical artistic movement – since my earliest works I have thought about Surrealism. And dreams are the vehicle of any creation.

A: Alma, a theme in Not’s work is hybridity, such as in Half Man Half Animal (L’asen da Sent) / Turning into a Donkey (1998–2012) or HEADS (2013). Could you discuss this assemblage approach to sculpture?

AZ: The idea of objects, people or animals in flux is central to Not’s artistic language and can take the form of anthropomorphic depictions as in Half Man Half Animal. In doing this he creates a sense of movement, as the subject passes from one state to another. Dynamism is ever present in Not’s work and this is also a comment on time. Not often combines two things that seemingly have nothing to do with each other. For example, in the HEADS series, the profile is over-sized, whilst the chimney is a miniature. He depicts tension in his pieces, which is frequently a result of bizarre combinations of objects, or of exaggerated scales.

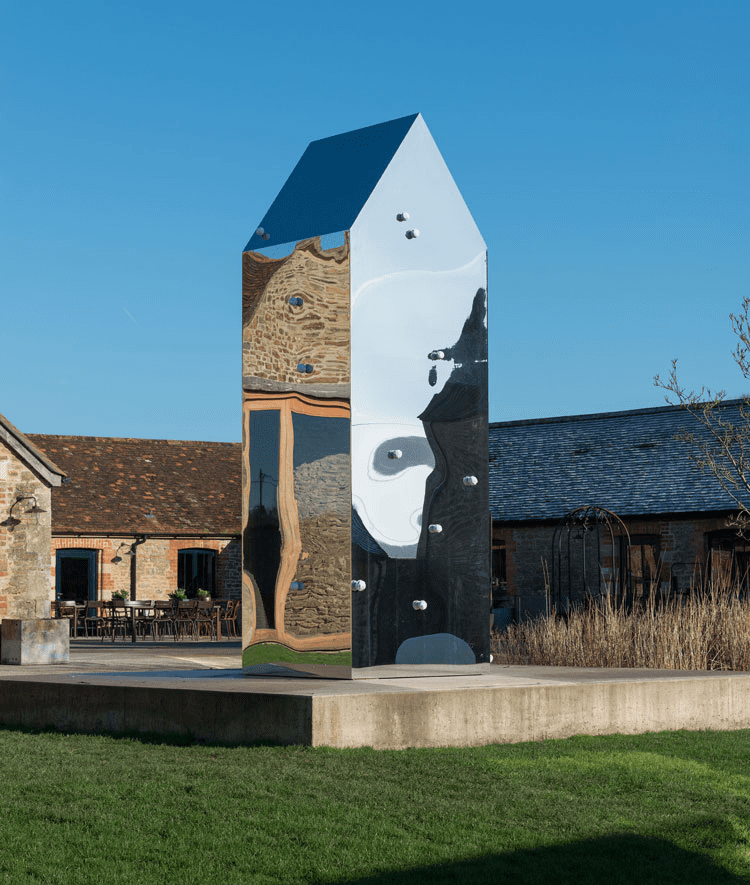

A: The term ‘SCARCH’ – an amalgamation of the words Sculpture and Architecture – is coined by Not and is used to describe immersive, site-specific structures. Could you tell us more about the practice?

AZ: There are many architects who make buildings that are sculptural. Not makes sculptures that are highly architectural. The SCARCH pieces might have a function that is poetic rather than necessary – for example a House to Watch the Night Skies (2006) – they might not abide by health and safety regulations – for example a 13 metre exterior staircase without railings on his House to Watch the Sunset (2005); they might have an underground window that looks at a wall of earth as in JOSUJO, Disappearing House (2007). Being an artist gives him the ultimate freedom. The best way to see more of this if you are in Europe is to visit his Sculpture Park in his home-village in Sent, Switzerland. Here you can find bridges made of aluminum donkey heads, a hair-covered tower, a Murano-glass house and much more.

A: These buildings often inhabit a place of observation – they are towers to watch the sunset or houses to view volcanoes. The process of looking and watching recurs. Where does this come from?

NV: They originated from my very early youth, when I was constructing tree houses. Years after, I returned to this practice and have approached architecture in unconventional ways, for example, a House to Think, a House to Watch the Sunset (2005) or a House that is not a House.

A: Your later works such as the neon script of Che Bellezza Esa Na Sana Che Bellezza Hanna (What Beauty, They Don’t Know What Beauty They Have) (2018) and the ceramic inscribed vessel Ün Tschiervi (2018), incorporate words. What does language offer up to your pieces?

NV: I have always incorporated the Romansh language in my works. My mother language is Romansh (the 4th national language in Switzerland and spoken only by 60,000 people) and preserving the language isn’t only our duty, but is fundamental to our own culture. In my Foundation in the village of Ardez, I have a library with a collection of many of the earliest Romansh books all of which were printed in the Engadin.

A: The recently published Skira book, edited and written by Alma Zevi, is the most comprehensive title to date of your oeuvre. What did you learn whilst working with Alma – did it make you see anything differently? And to Alma, can you tell us about your experience of writing the book?

NV: When Alma was writing the book surprises occurred constantly. She saw connections between my historical and more recent works that I wasn’t aware of, like one of my recent paintings Man Balancing 1 Snowball (2019). Alma immediately connected it to the time I had the circus in Rome (1968).

AZ: The book started as a patchwork of texts, from my BA thesis on Not’s relationship to the Engadin, to a number of museum catalogue essays. I love writing, and Not generously gave me carte blanche to interpret his work in whatever way I wanted, which was a little intimidating but also empowering. This was a very ambitious project and as a result the book is almost 500 pages long. The nature of Not’s work is that the more you discover, the more you want to delve further. I am an art historian and started working in Not’s studio after graduating from the Courtauld Institute in 2010. That academic, scholarly language and research fused with the personal stories that I gathered having spent huge amounts of time with the artist.

A: What’s next for you both? What projects should we look forward to?

NV: Many simultaneous projects, alongside having exhibitions in different countries. An intervention in a park in Rio de Janeiro and revelations in the South of Japan. Towers in Switzerland and Stairs in Austria.

AZ: Following a busy summer with book launches at the Beyeler Foundation and Tarasp Castle, the next stops for Not and I are London and Venice with events at Serpentine and Palazzo Grassi. Aside from my book, I am actively involved with a number of museums and institutions, including London’s National Gallery as we approach their bicentenary year in 2024.

Not Vital: Sculpture by Alma Zevi | skira.net

Image Credits:

1. Not Vital, Moon, (2004).

2. Not Vital, Camel (2018).

3. Not Vital, Head No. 3 (2013).

2. Not Vital, Cannot Enter Cannot Exit, (2020). Installation view ‘Not Vital. SCARCH’ Hauser & Wirth Somerset 2020 Photo: Ken Adlard.

3. Not Vital, House to Watch the Sunset (2005).

4. Not Vital, Calming Room (2018).